Books

The Moral Circle

Who Matters, What Matters, and Why

This book argues that humanity should expand our moral circle — that is, our conception of which beings morally matter for their own sakes — much farther and faster than many philosophers assume, for two related reasons. First, we should be open to the realistic possibility that a vast number of beings can be sentient or otherwise morally significant, including invertebrates and, eventually, AI systems, and we should extend at least some moral consideration to these beings accordingly. Second, we should be open to the realistic possibility that our actions can affect a vast number of beings, including beings who are far away in space and time, and we should extend at least some moral consideration to these beings accordingly as well. The upshot is that we should extend at least some moral consideration to septillions of beings, including and especially future nonhumans, with transformative implications for our lives and societies.

This book is available in print and audio.

Saving Animals, Saving Ourselves

Why Animals Matter for Pandemics, Climate Change, and Other Catastrophes

This book argues that human and nonhuman fates are increasingly linked. Our use of animals contributes to pandemics, climate change, and other global threats which, in turn, contribute to biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and nonhuman suffering. As a result, we have a moral responsibility to include animals in global health and environmental policy, by reducing our use of them as part of our pandemic and climate change mitigation efforts and increasing our support for them as part of our adaptation efforts. Applying and extending frameworks such as One Health and the Green New Deal, I call for reducing support for factory farming, deforestation, and the wildlife trade; increasing support for humane, healthful, and sustainable alternatives; and considering human and nonhuman needs holistically. I also consider connections with moral status, political status, creation ethics, population ethics, social services, infrastructure, and more.

This book is available in print and audio, and the print edition is available open access.

Chimpanzee Rights

The Philosophers’ Brief

This book makes the case for chimpanzee rights. Under current US law, one is either a ‘person’ with the capacity for legal rights, or a ‘thing’ without the capacity for legal rights. And currently, all nonhuman animals are classified as things. Focusing on two captive chimpanzees, Kiko and Tommy, we argue that this approach to legal status is unacceptable. We consider the four main conceptions of legal rights and personhood that US courts have affirmed: a species conception, a social contract conception, a community conception, and a capacities conception. We argue that the species conception fails, and that the other conceptions, plausibly interpreted, are compatible with chimpanzee legal personhood. We conclude that if we continue to classify every being as either a person or a thing, then we should classify chimpanzees as persons, not things. We close by considering future directions for animal rights.

This book is available in print.

Food, Animals, and the Environment

An Ethical Approach

This book examines some of the main impacts that agriculture has on humans, nonhumans, and the environment, as well as some of the main questions that these impacts raise for the ethics of food production, consumption, and activism. Industrial animal agriculture is much more harmful than alternative food systems. It kills hundreds of billions of animals per year; consumes vast amounts of land, water, and energy; and produces vast amounts of waste, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. These impacts raise difficult ethical questions. What do we owe members of other species, nations, and generations? And what are the ethics of supporting and resisting unnecessarily harmful industries? The discussion ranges over topics such as effective altruism, abolition and regulation, revolution and reform, individual and structural change, single-issue and multi-issue activism, and legal and illegal activism.

This book is available in print.

Articles

According to what we call the Emotional Alignment Design Policy, artificial entities should be designed to elicit emotional reactions that reflect the entities’ capacities and moral status, or lack thereof. This principle can be violated in two ways: by designing an artificial system that elicits stronger or weaker emotional reactions than its capacities and moral status warrant (overshooting or undershooting), or by designing a system that elicits the wrong type of emotional reaction (hitting the wrong target). Although presumably attractive, practical implementation faces several challenges including: How can we respect user autonomy while promoting appropriate responses? How should we navigate expert and public disagreement and uncertainty about facts and values? To what extent should designs conform to versus attempt to alter user assumptions and attitudes?

Experts have often assumed animals lack consciousness until proven otherwise, but some now suggest changing this presumption. Options include assuming consciousness in all animals, all living beings, all with neurons, all with complex cognition, or even all beings. I assess these options scientifically and ethically, arguing that different defaults make sense in different contexts. For example, a broad assumption of consciousness may be better for ethical theory and scientific practice, since it supports precaution and innovation. However, a narrower assumption may be better for scientific theory and ethical practice, since it works with existing evidence and institutions. By adopting multiple context-specific defaults, we can better serve both science and ethics.

This paper argues for ethical oversight in insect research. Despite the widespread use of insects in scientific and medical research, they receive little to no protection under existing animal welfare regulations. We show that many insects exhibit cognitive and behavioral markers of sentience and argue that, when there is uncertainty about whether an animal is sentient, we have a responsibility to consider welfare risks for that animal. We then explore how ethical oversight for insect research could be implemented by adapting existing frameworks for vertebrate research while accounting for the unique challenges posed by insects as research subjects. While extending oversight to insects would require overcoming numerous barriers, failing to do so risks both moral negligence and public mistrust.

Despite growing recognition of the importance of One Health, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development omits explicit reference to animal health and welfare. This report, produced by Stockholm Environment Institute and the NYU Center for Environmental and Animal Protection, argues that this omission undermines policy coherence and overlooks critical interconnections between human, animal, and environmental health. Drawing on expert analysis across all 17 SDGs, we identify three complementary pathways for integration: strengthening animal welfare consideration in current SDG implementation, introducing new targets and indicators aligned with existing Goals, and establishing a dedicated Goal on animal health and welfare. As governments prepare for post-2030 deliberations, systematic integration of animal health and welfare offers opportunities to address root causes of health, environmental, and development challenges.

This paper makes a case for insect and AI legal personhood. Humans share the world not only with large animals like chimpanzees and elephants but also with small animals like ants and bees. In the future, we might also share the world with sentient or otherwise morally significant AI systems. These realities raise questions about what kind of legal status insects, AI systems, and other nonhumans should have in the future. At present, debates about legal personhood mostly exclude these kinds of individuals. However, I argue that our current framework for assessing legal personhood, coupled with our current framework for assessing risk and uncertainty, imply that we should treat these kinds of individuals as legal persons. I also argue that we have good reason to accept this conclusion rather than alter these frameworks.

In their paper “AI Wellbeing,” Simon Goldstein and Cameron Domenico Kirk-Giannini argue that some language agents plausibly possess the capacity for wellbeing and moral standing even if they lack consciousness. My response is ambivalent. On the one hand, I am skeptical of theories of wellbeing and moral standing that lack a consciousness requirement. On the other hand, I agree with Goldstein and Kirk-Giannini (2025) that several leading theories of wellbeing and moral standing jointly imply that some language agents may be welfare subjects and moral patients and that this implication should be taken seriously. In fact, I argue that if we fully account for moral and descriptive uncertainty, we may need to lower the bar for moral standing even further, to include entities with only minimal forms of goal-orientedness or information processing. The question of whether and how to account for uncertainty might thus determine whether the arguments in “AI Wellbeing” go too far — or not far enough.

This chapter makes the general case for including animal welfare in local policymaking, with special focus on institutional and infrastructural change. We start by discussing the importance of animal welfare for the One Health framework, along with key questions about animal welfare. We then discuss general principles and policies that can guide cities in building multispecies urban infrastructure. For example, cities can implement bird-friendly building materials, improve road design and operation, provide guidance for incorporating animal shelter and habitat into green infrastructure, and shift their lawn maintenance practices. These and other policies have the potential to benefit humans, animals, and the environment alike.

We examine how society might respond to the possibility of AI consciousness by drawing parallels with human attitudes toward animal consciousness. Our analysis reveals that perceptions of AI consciousness will likely be influenced by appearance and behavior, social and economic roles, and moral biases. However, AI systems may benefit from their advanced cognitive capacities while facing challenges due to their non-biological origins. We argue that attitudes toward AI consciousness remain malleable, making this a critical moment for research and policy development. We call for urgent interdisciplinary research on the science of AI consciousness, public attitudes about this issue, and ethical frameworks for navigating potential societal disagreement and ensuring thoughtful preparation.

In this paper (co-sponsored by the Center for Mind, Ethics, and Policy; the Centre for the Governance of AI; and the Global Risk Behavioral Lab), we survey 635 AI researchers and 838 U.S. participants about the possibility of AI systems with subjective experience, as well as on the moral, legal, and political status of AI systems with subjective experience. Neither group predominantly believes such systems are imminent, but many forecast their existence within this century. Both groups support multidisciplinary expertise in assessing AI subjective experience and favor implementing safeguards now. While support for AI welfare protections was lower than for animal or environmental protection, majorities agreed that AI systems with subjective experience should act ethically and be held accountable.

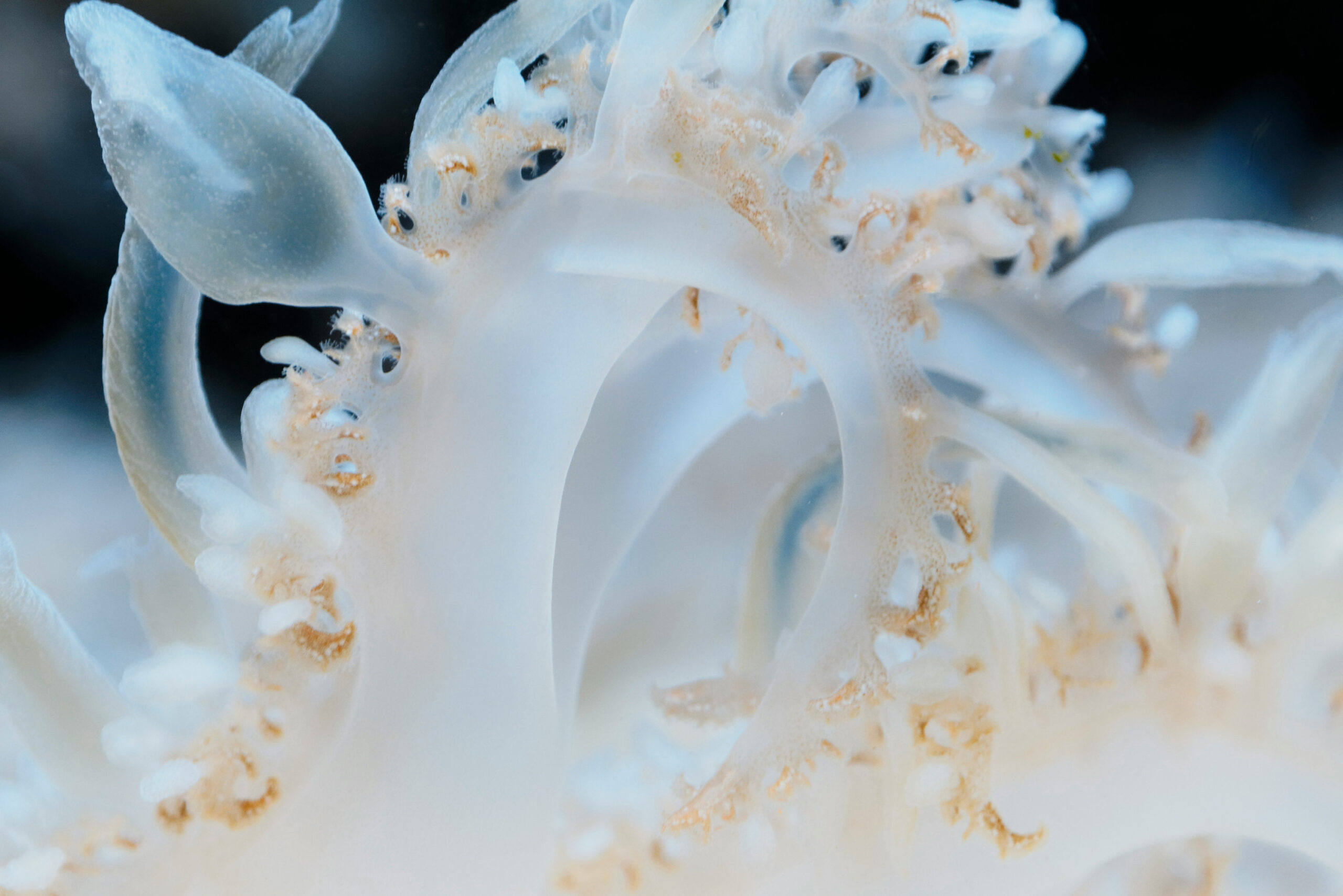

The emerging science of animal consciousness is advancing through investigations of behavioral and neurobiological markers associated with subjective experience across diverse species. Research on honeybee pessimism, cuttlefish planning, and self-recognition in cleaner wrasse fish provides evidence that consciousness may be widespread throughout the animal kingdom. Although the field faces uncertainties—stemming from the absence of a secure, unified theory of consciousness and the complexity of differentiating conscious from unconscious processes—these investigations underscore the value of open-minded, interdisciplinary inquiry. By exploring consciousness across taxa, researchers can collect valuable evidence and set the stage for a more inclusive understanding of the tree of life.

This chapter examines the ethical implications of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) for wild animals. While ART is widely used to support biodiversity, prevent extinction, and enhance genetic diversity, its effects on individual animal welfare are often overlooked. We argue that many wild animals have the capacity for welfare and thus warrant moral consideration. We then analyze the direct and indirect welfare impacts of ART, including the invasive procedures involved, the disruption of natural behaviors, and the ethical implications of prioritizing species survival over individual well-being. Given the urgency of biodiversity loss and climate change, ethical scrutiny of ART can help guide more just and effective conservation strategies that prioritize both ecological and individual well-being.

The field of AI safety considers whether and how AI development can be safe and beneficial for humans and other animals, and the field of AI welfare considers whether and how AI development can be safe and beneficial for AI systems. There is a prima facie tension between these projects, since some measures in AI safety, if deployed against humans and other animals, would raise questions about the ethics of constraint, deception, surveillance, alteration, suffering, death, disenfranchisement, and more. Is there in fact a tension between these projects? It depends in part on what sentient, agentic, or otherwise morally significant AI systems might need and what we might owe them. We argue that, all things considered, there is indeed a moderately strong tension—and it deserves more examination.

Agency and Moral Status

The Journal of Moral Philosophy (2017)

According to our traditional conception of agency, most human beings are agents and most, if not all, nonhuman animals are not. However, recent developments in philosophy and psychology have made it clear that we need more than one conception of agency, since human and nonhuman animals are capable of thinking and acting in more than one kind of way. In this paper, I make a distinction between perceptual and propositional agency, and I argue that many nonhuman animals are perceptual agents and that many human beings are both kinds of agent. I then argue that, insofar as human and nonhuman animals exercise the same kind of agency, they have the same kind of moral status, and I explore some of the moral implications of this idea.

Upcoming

This chapter surveys scientific, ethical, and legal issues that AI raises for animal welfare and rights. It opens with recent history and future pathways for AI, emphasizing emerging capabilities that could create significant benefits and harms for humans and animals alike. It then presents recent history and future pathways for animal ethics, emphasizing the extension of traditional questions about welfare and rights to invertebrate and wild animal populations. Finally, it examines recent history and future pathways for animal law, emphasizing efforts to recognize animals as sentient beings and legal persons and reform farming, research, and other practices. Considering these developments together illuminates the opportunities and challenges this technology will raise for animals.

Existing AI ethics frameworks focus largely on human interests, creating an urgent need to include nonhuman animals as stakeholders as well. This project examines how AI will affect nonhuman animals across sectors, with special focus on farmed animals, wild animals, urban animals, and other large and neglected nonhuman populations. It maps current and emerging AI applications that will interact with animals, assesses the ethical issues they raise, and identifies gaps in existing research and policy. The project will produce concrete, evidence-based recommendations and aims to inform both research and policy related to AI governance. (This project is a collaboration with the Jeremy Coller Centre for Animal Sentience at the LSE.)

Farmed and wild animals are among the most impacted and neglected stakeholders in health and environmental policy, and cities are uniquely positioned to act as policy innovators, incubators, and influencers. Yet the potential for cities to improve animal welfare, public health, and the environment remains largely untapped. Through procurement, infrastructure, conflict management, emergency response, and public education, cities can make significant progress for humans and nonhumans alike. Combining rigorous argument with engaging storytelling, this book develops a clear theory of change and shows how local policy can integrate animal welfare into mainstream governance while strengthening public health and environmental outcomes.

This chapter examines whether, and how, animals should fall within the scope of deontological moral theory. It surveys influential deontological views that include and exclude animals based on cognitive or relational features. It then assesses whether such stances are defensible and how animals might plausibly feature in deontological views moving forward. Finally, it explores the implications for killing, letting die, agriculture, experimentation, and political institutions. Throughout, the chapter emphasizes the theoretical importance of empirical and moral uncertainty for deontology and the practical stakes of extending deontological concern to animals.

This chapter examines the question of whether animals have moral rights, exploring its theoretical foundations and practical implications. Many humans acknowledge that animals matter morally, yet they often deny that animals possess rights in a robust sense. We survey key arguments for and against animal rights. We then consider which animals might have rights, which rights they might have, and how strong those rights might be. Recognizing animal rights could have far-reaching consequences for law, policy, and society. While moral and scientific uncertainty persists, we argue that this uncertainty should not prevent us from taking seriously the possibility that our current systems systematically violate animal rights and that we have an urgent responsibility to reassess and reform our treatment of other animals.

This chapter examines the moral, legal, and political standing of animals, plants, and fungi in the context of climate justice. While the intrinsic value of nonhuman animals is increasingly recognized, skepticism persists about plants and fungi. We explore recent trends in ethics and science, including the “marker method” for assessing consciousness in nonhuman animals by searching for behavioral and anatomical properties associated with conscious experience in humans. Highlighting the complexities of plant and fungal cognition, behavior, and interdependence, we argue that these beings warrant further investigation despite the methodological challenges that they raise. We also explore implications of their potential moral, legal, and political significance in a world reshaped by human activity.

This report outlines welfare-centered local policies for managing human–wildlife conflict in cities. Aimed at U.S. municipalities (with broader relevance), it defines key concepts, situates conflicts on a spectrum from disputes to deep-rooted tensions, and stresses that harms often flow to animals as well as people. It explains local authority and constraints, then offers guiding principles—do no harm, prevention, coexistence, careful language, transparency, evidence-based adaptation, and equity. A practical menu follows: wildlife-sensitive design, bird-safe buildings, lighting and waste reforms, humane population management, emergency response and rehabilitation, and citywide planning and governance. The goal is durable, humane coexistence across urban communities.

This paper examines how to set priorities among a moral community that now plausibly includes all vertebrates, many invertebrates, and soon a wide range of AI systems. Beginning with forced-choice cases—saving a bat versus a bee, or an organic bee versus a robotic bee—I argue for a precautionary approach that grants moral consideration to any entity with a realistic chance of mattering. I then assess four factors bearing on priority-setting: probability of moral significance, magnitude of moral significance, relationality, and practicality. Each factor is important but risks anthropocentric bias. I propose using a Rawlsian “original position” heuristic to approximate impartiality.

When we judge that a dog is better off than a pig, we make an interspecies welfare comparison. When we judge that a dog is better off than a robot, we make an intersubstrate welfare comparison (in this case, between a being made out of carbon and a being made out of silicon). We survey the challenges associated with comparing the welfare impacts across species and substrates. Then, given that these challenges are likely to be ongoing and that one important purpose of interspecies and intersubstrate welfare comparisons is to inform decision making, we map out alternative strategies for accomplishing this goal. In particular, we examine the possibility of using multicriterial analysis and other tools for making decisions involving seemingly incomparable goods for making progress on this topic.

Traditional classifications of animal research as invasive or non-invasive focus on physical impacts, often neglecting social, cultural, and psychological harms. We introduce a framework centering these non-physical dimensions, using wild primate capture and release as a case study. Whether or not these protocols cause physical harm, they can disrupt sociocultural dynamics and behavioral patterns — destabilizing group hierarchies, displacing dominant individuals, and affecting traits like neophobia and neophilia, with consequences for community cohesion and cultural traditions. Other methods, including drones and camera traps, pose similar risks. Our analysis calls for ethically attuned practices that respect the complex social and cultural fabrics of animal communities.

Recent procedures transplanting organs from pigs into humans have reinvigorated hopes around xenotransplantation. Yet ethical analyses have thus far focused primarily on humans, neglecting questions about the animals involved. This paper argues that xenotransplantation is problematic even under the standard 3Rs framework for animal research, and that this practice is clearly impermissible under more demanding frameworks emphasizing harm-benefit analysis and principles of respect, compassion, and justice. We critique common justifications for the practice and identify critical ethical considerations—including accurate language, financial interests, and commitment to animal-free alternatives—that must be addressed moving forward.

The Moral Problem of Other Minds

The Harvard Review of Philosophy (2018)

In this paper I ask how we should treat other beings in cases of uncertainty about sentience. I evaluate three options: first, an incautionary principle that permits us to treat other beings as non- sentient; second, a precautionary principle that requires us to treat other beings as sentient; and, third, an expected value principle that requires us to multiply our degree of confidence that other beings are sentient by the amount of moral value that they would have if they were. I then draw three conclusions. First, the precautionary and expected value principles are more plausible than the incautionary principle. Second, if we accept a precautionary or expected value principle, then we morally ought to treat many beings as having at least partial moral status. Third, if we morally ought to treat many beings as having at least partial moral status, then morality involves more cluelessness and demandingness than we might have thought.